Madame of Horror

Originally published in GoreNoir Magazine

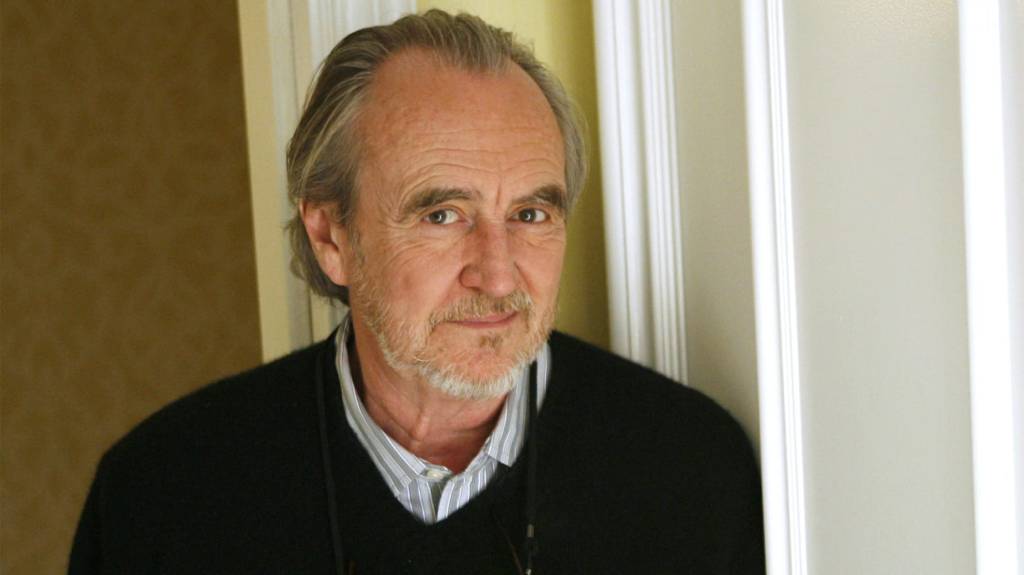

Wes Craven was a true visionary, gone too soon. He brought us two of the most pivotal and game changing horror franchises with A Nightmare on Elm Street and Scream. He had a way of taking what we thought we knew about the genre and changing the rules, raising the stakes, and surprising us. One change that was vital, was creating female characters who were strong, ass kicking survivors. Until Wes, final girls were arm flailing, tripping over nothing, screaming pairs of breasts, who survived almost by chance. Though Wes didn’t start his career off with any apparent feminism. He burst onto the scene with gratuitous gore, making people think he had to be some sort of monster. But, if you listened to any of his interviews, he may have been the opposite.

His first horror film, Last House on the Left, was downright unwatchable to many, depicting violence, sexual and otherwise, toward women. You could argue that revenge horror is empowering, but unlike the appropriately titled, 2018 film “Revenge”, this one was way too heavy on the torture and violence, leaving you unable to even appreciate the pay off. It was this “don’t cut away” approach and Craven’s own irritation with how quickly characters died in films, that made the movie so unsettling. At the height of the Vietnam war, he noticed Americans becoming too immune to the violence around them. He didn’t want to shy away from the realism of torture and death, giving the audience way more than what they bargained for. It was that unfiltered approach that gave Wes Craven’s films something to connect to. Growing up in a strict religious household, where films along with dancing and drinking were forbidden, he knew what it was like to see life through a smoke screen, and maybe that’s what made him work to depict real life, as is, in his films.

“I think the benefits of seeing that is that it reaffirms reality rather than reaffirming a fantasy… and my feeling was, it’s time to stop dreaming. And I guess that’s become the theme of my entire work- it’s time to wake up.” -Wes Craven, interview with Terry Gross for Fresh Air, 1987

In a world where horror films are often looked at as trash, unnecessarily showing violence and gore, and perhaps causing more harm in the world, Wes saw the good in them. He thought of horror films as being a much needed release of fear, and called them “devices for dealing with the chaotic danger of existence.” He would explore this theme more, with 1994’s New Nightmare, which he co-wrote, centering for the first time around the actors, not the characters of his best known film, A Nightmare on Elm Street. The original 1984 slasher, written and directed by Craven, centered around Nancy Thompson, who was the first final girl to use her brain and actually think “not in My story.” Even Halloween’s Laurie Strode, though shy and studious, seemingly fought off Michael Myers play by play. She was never a step ahead of him, the kind of premeditated combat shown by Nancy, whose now iconic line “I’m into survival” I always found as cheesy and eye roll inducing as most of the acting in the film. She was basically a child; what did she know about survival? As an adult, I now realize that’s the point entirely. She shouldn’t have to. But because of what has happened to her, she has been forced to grow up fast, and she doesn’t sit around crying with a woe is me attitude; she gets the fuck up and learns to fight. Alcoholic mother and divorced parents aside, a man has been forcing himself into a place where she has no control over: her dreams. Where are we more vulnerable than when sleeping, where we should be able to let down our guard and turn off our minds.

Using the advantage of innocence and purity in siding with our main character was nothing new to slashers, but giving her a bite was. Nightmare turned the rule of women in horror on its head, killing one of the boyfriends (Depp) in a way that showcased his weakness, and leaving another helplessly watching his girlfriend be killed, with only the option to flee the scene. There is no knight in shining armor to come save the women. In fact, everyone just seems to stand in their way. Not even Nancy’s dad, who is maybe the best of the Elm Street parents, believes her when she tries to enlist his help. Women are, historically, looked at as hysterical when they try to come forward with anything, something that still echoes today with sexual assault victims being met with skepticism. The take away from Nightmare is that the only way to beat your demons, is to face them. Any assault survivor can tell you that. Nancy learns in the end, what so many of us take way too long to learn, that you yourself are your biggest weapon. You create your own reality, and something can only destroy you if you let it. Nancy Thompson has become a symbol for survivors. Heather Langenkamp, who portrayed Nancy in all of the films that included her, has said that fans often come up to her and tell her that her character helped them with a problem in their own lives. That using her as a role model, helped them defeat their own “Freddy”. Pretty powerful stuff.

Freddy Krueger has become such a pop culture phenomenon, more so than any other killer, due in part to his snappy one liners, mixing horror with comedy, and creating a cult classic. But in a genre that glorifies and romanticizes the killers, Wes managed to give us female fighters to look up to and to root for. Over a decade after Nightmare, Wes brought us arguably, the best final girl of them all, Sidney Prescott. He directed Kevin Williamson’s screenplay, Scream, in 1996. It redefined the slasher genre, and dove even deeper into the metaphysical than New Nightmare did, making the characters self aware of the type of horror film they were in.

“…and it was kind of in a place where it needed to be satirized, at least before you went onto something new…so in the sense that you say we know horror films have been either boring or stupid or predictable, there’s kind of a rush of relief because they know, well, at least they’re in the presence of somebody who is smart enough to figure that much out. Now let’s see if they can do something new.”– Wes Craven, interview with Terry Gross for Fresh Air, 1998

In Scream, we got to explore the rules we all knew existed, but said out loud for the first time by the characters. Most rules, like saying “I’ll be right back” held up, except one, involving our final girl, Sid. The virgin rule. This incredibly sexist rule of slashers, where any girl who has sex or is openly sexual is promptly punished for her sins, is wiped away in this film. Sid discovers that the killer was her James Dean-esque boyfriend, Billy Loomis, all along, and serves up justice of her own, but not before scoring with the sexy serial killer. With Sidney, we have the same sense of trauma, and ptsd for that matter, mostly due to her mother being brutally murdered. She isn’t dealing with things well, and her shitty boyfriend forces her to. Sid is a breathe of fresh air in a sea of desperate, helpless scream queens. She comes back every film, dealing with more and more trauma, but with grace. In the fourth film, she has written a book to help others cope, and in turn has to deal with even more death. The woman can’t get a break, but it’s enough to leave any other woman institutionalized, where Sid just keeps doing what she has to do to survive, and to shine.

Maybe that’s what made Wes’s legacy so great, his dedication to making us feel every little thing in his films. From creating characters who we can relate to, to showing us the grit and the real human struggle. Anyone in an abusive and manipulative relationship can relate to Sidney, finding out her boyfriend who she just let herself be so open and vulnerable with, was to blame for the death of her mother, and nearly herself. Anyone who’s been sexually violated, would have those moments resonate with them, when Nancy can’t even feel safe in a bathtub, never being truly alone and secure again. And these moments can still resonate with someone who hasn’t been in any kind of danger, but experiences it through the film’s hero. It stands to show that Wes was an incredibly empathetic person, and wanted us all to have that same connection when watching his films. Whether it was torture gore, black comedy, or hyper-campy 80s horror, Wes Craven put heart into everything that he did. Even when it was admittedly not the type of movie he would have watched, or wanted to do at the time, he had an insane understanding of the purpose of the project, and gave it all to deliver a work of art, and a message. We were lucky to share some of the same time on this planet as the director, and I, myself will always look to him for inspiration.

Thank you for Nancy, for Sidney, and for you, Wes Craven. We love you.

Leave a comment